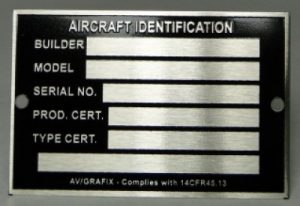

14 C.F.R. § 45.11(a) requires that a type-certificated aircraft have an identification or “data” plate issued by the aircraft’s manufacturer secured to the aircraft for that aircraft to be airworthy. Ordinarily, this isn’t an issue for an aircraft owner. But what happens when an aircraft is missing its data plate?

Perhaps the aircraft was wrecked. Or the owner purchased the aircraft as salvage. This can leave an aircraft owner in a tough spot: The aircraft may be in a condition safe for flight, but it isn’t flying anywhere without a data plate.

So, what can an aircraft owner, and the maintenance provider who may be assisting the aircraft owner, do? Well, one option is to contact the aircraft manufacturer and request a replacement data plate. Unfortunately, manufacturers are always concerned about product liability exposure. This makes a manufacturer reluctant to issue a new data plate. The manufacturer doesn’t want to expose itself to potential liability for an aircraft whose condition it has not been unable to verify. As a result, this option is seldom successful.

Another option that may tempt an aircraft owner or maintenance provider in this situation is to simply purchase another wrecked or salvage aircraft that is the same make and model. Then the purchased aircraft’s data plate can be removed and installed on the other aircraft missing its data plate. After all, this seems like a logical and reasonable option to get an aircraft that may be in perfectly safe, flyable condition back in the air. Right?

Unfortunately, the Federal Aviation Administration (“FAA“) doesn’t agree. And a decision by the National Transportation Safety Board (“NTSB”) affirmed the FAA’s position that this option is contrary to the regulations.

The Case

In Administrator v. Tre Aviation Corporation and Robert E. Mace, Tre Aviation Corporation (“TAC“) purchased a Bell 206B (serial number 3570) helicopter that was missing a data plate. Although Mr. Mace tried on behalf of TAC to obtain a data plate for the aircraft from Bell, not surprisingly that was unsuccessful.

So, Mr. Mace decided that TAC would use the helicopter for its parts. Later, Mr. Mace, again on behalf of TAC, purchased another Bell 206B (serial number 3282). 3282 was missing an engine and many other parts, but it did include a data plate. Although TAC purchased 3282 with the intention of repairing it, inspection of the aircraft disclosed that 3282’s fuselage was corroded beyond repair and required replacement.

Later, TAC did what would otherwise appear to be a reasonable thing to do to make the best of the situation. TAC replaced the corroded fuselage and tailboom on 3282 with the fuselage and tailboom from 3570. It also painted the registration number for 3282, on the tailboom of 3570.

During the replacement, TAC used only the upper right and left engine cowlings and the particle separator, as well as other “small” parts from 3282. TAC then applied for and received a standard airworthiness certificate for the aircraft from an FAA designated airworthiness representative. With that in hand, Mr. Mace, an A&P mechanic with inspection authorization, approved the aircraft for return to service.

Unfortunately, when Mr. Mace spoke with several FAA inspectors during the course of a subsequent inspection, he told the inspectors what he had done. Shortly thereafter the FAA issued an order revoking the aircraft’s airworthiness certificate.

Unfortunately, when Mr. Mace spoke with several FAA inspectors during the course of a subsequent inspection, he told the inspectors what he had done. Shortly thereafter the FAA issued an order revoking the aircraft’s airworthiness certificate.

TAC appealed the FAA’s order and, after a hearing, an NTSB administrative law judge (“ALJ“) affirmed the FAA’s order. The ALJ found that TAC’s apparent removal of the data plate from 3282 and installation on 3570 resulted in the aircraft being improperly identified. This improper identification meant the aircraft did not qualify for a standard airworthiness certificate. TAC then appealed the ALJ’s decision to the full NTSB.

The Decision

On appeal, TAC argued, among other things, that it had simply repaired the aircraft and that replacement of the 3282 fuselage was simply replacement of a component rather than switching the aircraft. In response, the Board initially cited 14 C.F.R. § 45.13(e) which states,

[n]o person may install an identification plate removed in accordance with paragraph (d)(2) of this section on any aircraft, aircraft engine, propeller, propeller blade, or propeller hub other than the one from which it was removed.

Consistent with this regulation, it also noted the importance of having an accurate data plate in light of airframe times and airworthiness directive compliance.

Turning to the specific facts of the case, the Board rejected TAC’s argument that it had simply “repaired” the 3282 aircraft. Rather, the Board determined the resulting aircraft was really the 3570 aircraft with the addition of a few parts, the registration number and data plate from the 3282 aircraft. As a result, the Board found that Section 45.13(e) specifically prohibited the replacement of the data plate in that situation.

The Board also rejected TAC’s argument that the “fuselage” was merely a component, rather than the “aircraft” itself. It observed that “[a] fuselage is a substantial aspect of any rotorcraft.” And consistent with Section 45.13(e) “the absence of the terms ‘fuselage’ and ‘airframe’ indicates a data plate’s installation on an airframe or fuselage or any other component designed to exist permanently on an aircraft is the same as the data plate’s installation on an aircraft.”

The Board also rejected TAC’s argument that the “fuselage” was merely a component, rather than the “aircraft” itself. It observed that “[a] fuselage is a substantial aspect of any rotorcraft.” And consistent with Section 45.13(e) “the absence of the terms ‘fuselage’ and ‘airframe’ indicates a data plate’s installation on an airframe or fuselage or any other component designed to exist permanently on an aircraft is the same as the data plate’s installation on an aircraft.”

The Board then confirmed that Section 45.13(e) precludes replacing virtually all parts and components of a wrecked aircraft and then attaching that aircraft’s data plate to the assembled replacement parts and components. And based upon the record, the Board determined that is exactly what TAC had done. Thus, it affirmed the ALJ’s finding that TAC had violated Section 45.13(e).

Conclusion

This is a tough situation for an aircraft owner to be in. It can also be difficult for the maintenance provider assisting the aircraft owner and trying to get the aircraft back in the air.

As with most cases, whether an aircraft is simply being repaired, or whether it is being completely rebuilt with replacement parts and components, will be decided based upon the unique facts of each particular situation. If an aircraft owner in that situation suggests or requests a remedy that involves removal or installation of a data plate, maintenance providers should be wary.

In this case, the FAA was only taking action to revoke the aircraft’s airworthiness certificate. However, oftentimes the FAA will also be pursuing action against the mechanic who worked on the aircraft or returned it to service as well.

If you are asked to replace or install an aircraft data plate, make sure you understand the regulations and the risks before you agree to swap data plates.